For my personal challenge to read books in other languages than English, I’ve been greatly helped by an online book discussion group hosted by Emma of Words and Peace, who this year also took up the hosting of beloved blog event Paris in July. For our summer read, we had already decided to take a novel by Jules Verne, and I voted for Voyage au centre de la Terre (Journey to the Center of the Earth) since it was one I didn’t know from English translation.

Language-wise it was a good decision; the sentence structure was not too hard to follow, though I had to look up some words (easy on an e-reader). There was a lot of specialized geological and paleontological vocabulary that I could try to interpret, or just skip, as learning the names of various kinds of rocks or ancient creatures is not likely to be useful in my future life and reading.

As an adventure story, it had some drawbacks. Nearly half the novel goes by before we even get under the ground; a good part of the book takes place in Iceland, where the exploring party goes in search of a passage into an extinct volcano, indicated through deciphering a cryptogram in an old book (the latter a fun sequence). Here is where a long-ago Icelandic explorer claims he began his own journey beneath the earth. This was interesting as a travelogue of 19th century Iceland, but not quite what I expected from the title.

Then, there is the cast of characters. Our first-person narrator is Axel, nephew of the somewhat crazed professor Lidenbrock who has instigated the expedition, The third member of the party is a laconic Icelandic hunter, Hans, who they have fortunately brought along because he saves their bacon many times over, while hardly uttering a word (and then only in Icelandic). With the professor’s monomania making him a poor conversation partner, there is little dialogue, so the book is mainly composed of Axel’s observations and descriptions.

Axel makes up for the others in his emotional fervor. When not longing to return to his lovely fiancée, he is worrying about how they will get to their objective and how they will get back — and not without reason! At one point, in spite of the professor’s airy assumption that they will find water along the way, they run out and Axel practically dies of thirst. Another time, he becomes separated from the others, and is lost in the dark and injured. By chance and a bit of astute scientific reasoning involving acoustics they find each other again. Passages like this, as Emma suggested, should be categorized as horror — what a nightmare

Though Verne did his best to be scientific, making use of then-current technology and reasoning, he had to fudge the impossibility of the venture by making light sources and food stores improbably long-lasting; it was also implausible how the explorers were able to so precisely calculate their location and velocity, even sometimes without the use of instruments. Not much was known at the time about the depths of the earth, and as climbing through uninhabited rocky passages is not really the most thrilling subject for a book, after a while Verne tries to liven things up with speculative and imaginative passages. For vague reasons, the theory of a molten core to the earth has been dismissed, so it conveniently stops getting warmer after a while, and following the lost-in-the-dark sequence a massive underground sea is discovered, with similarly convenient ambient light source somehow produced by electricity.

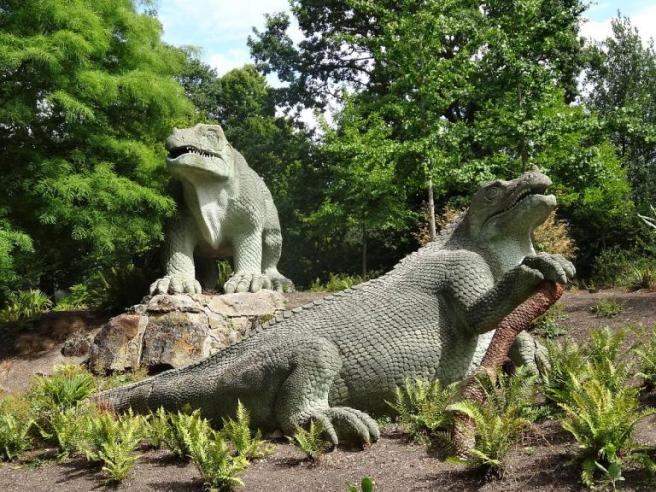

The geological voyage underground is at the same time a paleontological voyage into the past, into the layers where past ages of the earth are preserved. However, although some living things appear (again improbably) in the depths, including the forest of giant mushrooms pictured on the cover of the edition above, not much interaction happens. Axel has a lengthy hallucination about these former times, and there is a battle between antediluvian sea-creatures that provides some excitement, plus a brief glimpse of surviving mastodons and giant humanoids. Sadly, the explorers run away from these before any close encounter can occur; Verne seems determined to keep all ancient specimens as a safe distance, for observation only.

The explorers construct a raft of partly-fossilized wood and go on a voyage that turns out to be in the wrong direction, AGAIN — the professor is always making these bad decisions — but are blown backward in a storm (another terrifying sequence) that conveniently lands them where they should have gone in the first place. Here, after the lengthy backs and forths of the first part, Verne picks up the pace about 1000% and returns us to the surface within a couple of chapters, by means of our explorers emerging (impossibly, but never mind) from a live volcano in another part of the planet. They did not actually make it to the center of the earth, but at least the Professor’s wanderlust seems to have been satisfied.

An introduction by Simone Vierne gives some helpful historical context to Verne’s writing, and argues at length that his story is a picture of initiation. It does indeed contain many features of an initiatory journey, with its trials and terrors, but unfortunately, none of the characters could be said to really be transformed by it. They seem to come out exactly the same as they went in, which is not the point of initiation. Nor is there any encounter with the numinous or transcendent, or any growth in self-knowledge or moral strength. After each of his terrifying experiences, Axel just carries on worrying again; and after each of his failures, the professor goes back to his pompous ways. If this is an initiatory journey, it’s one that has been emptied of its inner meaning and purpose.

But Verne wasn’t commissioned to write a story of psychological depth, rather to put some of the scientific ideas of his time into a story exciting enough to engage the interest of schoolchildren. The fact that being “under the ground” is a powerful symbol of venturing into the unconscious seems to have been neutralized by the relentless materialism of modern science. Today, it is our task to breathe life back into that deadening enterprise, which makes me wonder if the “Voyage” might be rewritten in a more satisfying, integrative vein.

However, for now it was an enjoyable way to explore one of the giants of popular literature and French culture (without, it must be said, ever actually touching France in the pages of the book — the protagonists are from Hamburg, and as noted above, spend most of their above-ground time in Iceland) and to link up with Paris in July. See here for another review from Chris, who read the book in English but hopped into our discussion in French, as usual with some great insights, images, and trivia. I’m so grateful for my fellow explorers, who helped me to get through the version originale and to have fun doing it!

Have you read anything by Jules Verne? What did you think?

Read for #parisinjuly2023, also one of my #20booksofsummer23

Thanks for the review. I have read his famous Around the World but that’s it. This summer on a plane trip I met another fellow reader who says Salgari is more ignored but better when it comes to writing adventure books.

Never heard of Salgari, so I’ll have to look him up. It will have to be in translation though!

Thanks! I need to finally try him. What do you suggest: the fist book in the Sandokan series?

But then he will be for a summer in Italy challenge! LOL

A great summary, Lory, bringing up a lot of what I thought about this. The readalong (though I wasn’t strictly a participant) was a good excuse to try a Verne I’d not yet sampled in any form, so thank you, both you and Emma!

It was great to have you along even for part of the discussion!

I am always impressed by people who can read in another language!

I found the idea of this being an initiation story quite interesting.

It was interesting and something that had not occurred to me. Many myths of initiation involve a voyage into or encounter with the Underworld, though.

Thanks so much for this superb in-depth review!

So glad you liked it, Emma. And I’m so glad we read this book!

I think my comment got eaten (WordPress hates me) but while I assume I read this and Around the World as a child, I don’t remember either. However, the PBS miniseries of Around the World in 80 Days, which aired recently, was quite enjoyable and if available online, you should try it with your son.

Argh, I am sorry. I would like to watch 80 Days! My son read that in English class for school, which I found odd, because it was translated from French. Of course it’s about an Englishman, maybe that was the idea.

I’ve read Around the World in Eighty Days which I enjoyed; also this one but ages ago, and I only remember Axel’s constant reluctance (did he also grumble?). I think too that these are meant to be pure adventure, with not terribly much depth. Great job on getting it read in French! I had French for four semesters at University but have lost touch since so can only broadly decipher basic writing.

I studied French for ten years but never became fluent. I’m convinced now it was because I was afraid to make mistakes. It’s impossible to learn a language that way! Plus, I was too impatient with my slowness at reading. Now, I have learned to embrace mistakes and slowness and it goes much better. Verne is about my speed now so that was a good match!

That’s the case with me and languages too. I have been working on Korean (and to a lesser degree Japanese) via duolingo but tend to skip speaking exercises at times. With the reading, you’re right, speed comes when when starts to read irrespective of mistakes.

I’m so impressed that you were able to read this book in French. It seems to help me a lot to read books with others.

As I said, it was a good choice language-wise. The more I read the easier it gets, it just takes me a long time to feel more fluent. I never had the patience when I was studying French.