This essay was previously published in the now-defunct online journal Enchanted Conversation.

In fairy tales, marriage has a double nature. Its most well-known aspect is as a sign of completion, fulfillment and union; the end of the story, beyond which no more need be told. Cinderella, Briar Rose—this is what we mean when we say “fairy-tale marriage,” an ideal vision of prince and princess in perfect, unclouded harmony.

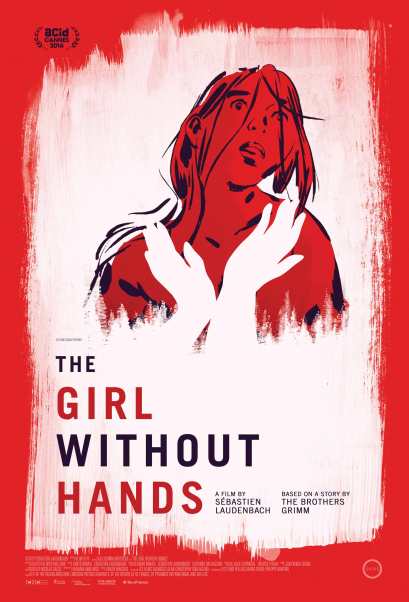

Yet in many tales, the marriage of the protagonist actually initiates a period of trials and suffering. In the Grimms’ “Allerleirauh,” a king seeks to replace his dead wife by marrying his own daughter. She flees in horror, utterly alone. “The Girl Without Hands,” also from Grimm, tells of a miller’s daughter who has been disfigured by the Devil. Though she marries a king, who gives her silver hands, she remains unhealed and helpless, and must again become a wanderer.

Such tales remind us that marriage is not only a singular event, but a new and challenging state of being, one which requires preparation, alertness and effort. Seeking to enter such states is perilous, and fairy tales depict in no uncertain terms the dangers.

They also describe the remedy. When we have crossed a threshold prematurely or unconsciously, a period of exile may be called for, a time to let the regenerative power of nature do its work. The handless maiden, cast out of the palace, spends seven years in the forest, after which her hands grow back once more. The king, who has also been wandering and searching for seven years, is reunited with her and their child; the story ends “and they were married again.”

The tales suggest that marriage, the union of previously unrelated individuals, leads to an insecure place where we cannot rely on past understanding. A period of adjustment, represented as banishment, disguise, or disfigurement, follows; in struggling with such adversity, the soul is strengthened and enlarged, and a true marriage becomes possible.

So strong is our dependence on the intellect with its technical solutions—like the “silver hands”—that we often must be forced or tricked into abandoning it, in order to activate the power of true healing. Yet this power is always present when we dare to reach out to it. In a Russian version of the story, the girl drops her baby into a stream. Forgetting that she has no arms, she reaches in to save him; in that moment, she becomes whole. (1)

Healing is also needed in “Allerleirauh,” where the king’s strange desire signals that the ruler of consciousness is unable to reach out beyond the self and its immediate blood ties. Stuck in the past, he cannot move forward into an unknown future. Under such circumstances the soul cannot develop. The princess herself regresses into a beast-like state; she puts on a cloak made of pelts from all the animals of the kingdom, becoming the creature Allerleirauh.

Beneath this protective covering she conceals golden treasure, the essence of her being. But even when brought into the household of a king, she does not immediately reveal her true nature, choosing instead to work in the kitchen. Only when the king sees through her disguise does she agree to marry him. Unlike the old king, he is able to expand his consciousness into new and unheard-of possibilities, to see his bride within the beast-slave Allerleirauh. Thus the danger that threatened at the beginning is averted, and the aborted marriage can be completed.

Frequently, it is not the protagonist of the story, but her lover or bridegroom who appears in disguise, as in “The Enchanted Pig,” a Romanian tale. A princess reluctantly marries a great Pig, who has been revealed by a prophecy as her husband. Once they reach their new home, she is delighted to discover that at night he appears in human form. Yet she is not satisfied with this situation. Meeting an old witch, she obtains a charm to keep her husband human.

When a creature takes on human form at night, it indicates that he appears differently to night-consciousness, to dream and vision; that is, he is a spiritual being (2), the higher aspect of the self which is not immediately apparent to our senses. There is a strong drive in the soul to drag this aspect prematurely down into the earthly, daytime world.

Disaster, of course, ensues. In the story, the Pig-husband wakes, and berates his wife, for only three more days would have ended the spell that bound him. He disappears, telling her “we shall not meet again until you have worn out three pairs of iron shoes and blunted a steel staff in your search for me.”

The princess, having in her ignorance breached the boundary between the daytime and nighttime worlds, now must undergo an initiation to prepare her for the higher life. She journeys through the realm of the heavens, visiting the houses of Moon, Sun and Wind, penetrating the hard iron and steel of earthly matter through persistent and faithful effort. At last she is ready to return with her husband to her own kingdom, and to rule “as only kings rule who have suffered many things.”

Marriage in fairy tales often activates forces of opposition, a Devil or witch who seeks to separate the newly united couple. However, these adversaries actually aid in bringing about the very thing they seem to work against, for they call forth in the hero or heroine previously unknown strengths and capacities, needed to enter into a new state of being. Is it only our resistance to change, our reluctance to exert ourselves, that makes such a figure appear as an enemy?

In a tale from Hungary, the demonic Eisenkopf helps a poor peasant lad on the condition that he promise never to marry. His father, though, presses him into marriage with a village girl. When Eisenkopf appears at the wedding, the terrified bridegroom runs away.

He travels far beyond the mundane world he has known, meeting the acquaintances of marvelous abilities—Quick-ear, Iron-strong, and World’s-weight—who ultimately defeat his adversary. Not only that, but he finds his true love in the house at the world’s end. None of this, the expansion of his world, the discovery of new abilities, the finding of a companion dear to his own heart rather than his father’s, would have happened without the intervention of Eisenkopf. The boy’s own need called the demon forth, so that he might grow beyond himself. Only then is he able to rightfully enter the realm of marriage.

Bridging matter and spirit, self and other, childhood and adulthood—the rewards of marriage are great, but they can only come to those who have the strength to bear them. If a fairy-tale marriage brings trials and misfortune, this may in fact be the greatest gift of all.

Notes:

(1) For a study of “The Girl Without Hands” and other related stories, see Gertrud Mueller Nelson, Here All Dwell Free (New York/Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 1999).

(2) A Native North American legend, “The Dirty Bride,” makes this meaning explicit: a boy marries the dirty-faced “Corn Smut Girl,” who reveals her radiant beauty to him only at night. After living with him for a time, she vanishes back into the spirit world and their home is enshrined as a holy place. The myth of Cupid and Psyche is an archetypal example of all such divine-mortal couplings.

Wow. I’m always amazed at how much there is in fairy tales about life, and this on marriage was fascinating to read.

this,

If a fairy-tale marriage brings trials and misfortune, this may in fact be the greatest gift of all.

is such a ‘realistic’ portrayal of marriage as well, don’t you think? (I look back at the trials in my marriage, and find that, despite not having liked going through them at the time, they’ve been blessings that have made my marriage stronger.

Very true, in my experience as well. As some have pointed out, the glorification of romantic love in our secular society has usurped the place that used to be held by worship of the deity. It’s no wonder that when those projections are placed on a fallible human being, things easily go wrong. But working them through can be incredibly rewarding, if difficult.

What a truth, Lory

I have more time today. I love what you said there, “the glorification of romantic love in our secular society…” I too believe this has robbed us of something deeper, a more nuanced view of love that we learned from childhood through fairy tales, other stories, folk songs, art, etc. Not much is said about the difficulties and rewards of marriage life, -even parenthood-.

Fairy tales are not ‘just’ for children, that’s for sure.

Fairy tales have so much to teach us. I’m still learning.

Really fascinating. Your depth of understanding is fascinating, and I haven’t encountered some of these fairy tales. Never heard of “The Enchanted King.”

‘The Enchanted Pig” is one of my favorite stories from the Red Fairy Book (Andrew Lang’s collections, credited to him but his wife did most of the translating.) I was interested to come across the recent musical version when looking for images as I was not previously aware of its existence. So glad you liked the essay!